Ellen G. Landau: An Exclusive Interview with the Art Historian, Curator, and Writer.

- Lisa Lehman Trager

- Nov 6, 2024

- 15 min read

Updated: Nov 7, 2024

Background

Ellen G. Landau is an art historian, writer, and curator renowned for her expertise in 20th-century modern art. She has written books about Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner, Abstract Expressionist criticism, and the influence of the Mexican muralists on American Modernism. In addition, she has published dozens of articles and catalog essays, as well as received grants from prestigious organizations for her scholarship from entities, which include the National Endowment for the Humanities, Terra Foundation, Smithsonian American Art Museum, and won the Cleveland Arts Prize for Creative Achievement.

Recently, I had the privilege of talking with Dr. Landau about her career trajectory. The circuitous path leading to so many of her outstanding accomplishments is a great example of how unexpected, serendipitous events can often have a profound impact leading to new and unexpected directions. Her frequently humorous and entertaining stories reminded me of the saying, “Life is what happens while you’re busy making other plans.”

Formative years

Landau’s interest in art began when she was a girl growing up in Philadelphia. Even at the age of eight, she knew what she wanted and chose art classes over piano lessons. By the time she entered high school, her second major was studio art, and she was showing great promise.

She began her undergraduate studies at Cornell, majoring in Painting. By the second semester of her freshman year, she says, “I woke up one morning and had an epiphany that I was one of the best painters in my high school. That was it.”

The following year, she changed her major to Art History and never looked back. Initially, she aimed for a curatorial career. Her first job in the summer between her junior and senior years at Cornell was at the recently opened National Collection of Fine Arts (NCFA), today known as the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington DC. Hired as a museum guide, the museum was so new at the time, that “there were more guides than museum visitors.” To earn a stipend, she was required to do a research project.

Landau chose to write about the Washington Color School, which included artists like Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, Paul Reed, Tom Downing, and Howard Mehring. Her manager at NCFA and mentor, Pat Chieffo, had a major impact on her future professional life by introducing her to oral histories. She told Landau that she would have to interview the artists to fulfill her assignment. With Chieffo’s insistence, she ended up interviewing the artists who were still alive and talking with Jim Harithas, Director of the Corcoran Gallery at that time, a champion of the painters involved in the Washington Color School.

During her senior year at Cornell, Landau, seeking advice from Harithas who had also become a mentor, went to his office at the Corcoran Gallery, and asked him,

What classes should I take to be a curator? Should I get an art history degree, or should I get a degree in museology? And he said,” You want to work in a museum? You can come to work for me when you graduate.”

The following Spring, Landau got an offer letter to be hired as a Curatorial Assistant at the Corcoran Gallery.

My father drove me to Washington with a trailer and some furniture. I got an apartment with a person that I didn't even know. When I showed up for work, they said, who are you? I said, what do you mean, who am I? I'm Ellen Gross, and I'm here to work for James Harithas.

Harithas had resigned two weeks prior after a fight with the Board of Directors. Luckily Landau had the offer letter in hand, so they gave her the promised job of Curatorial Assistant. She proceeded to work for James Pilgrim, Chief Curator, and Walter Hopps, who replaced Harithas as Director.

In the following year she met her husband and stayed in Washington D.C. She continued her graduate studies at George Washington University and worked at the National Trust for Historic Preservation. As Landau tells it, one morning when she was about to speak for the third time at the Woodlawn Conference for Historic House Administrators, she realized that this was not what she wanted to do with her life and decided to go back for a Ph.D. in modern art.

Lee Krasner

Moving to Columbia Maryland, she continued her graduate studies at the University of Delaware which had, and still has today, a formidable American Art program. During the next six years, she had two children and, in the beginning, was driving down to Washington D.C. to teach twice a week, driving up to Delaware two days a week, and spending a lot of time in the Library of Congress to do her Graduate work. When it came time to choose her dissertation topic, Landau explained,

I went to New York to visit a friend from Cornell. Her boyfriend was Helen Frankenthaler's assistant at that time. One day, visiting him in his loft in Tribeca he asked me, “What do you want to write your dissertation on?” I said, I really want to write about Abstract Expressionism, but I haven't come up with a topic yet. And he replied, “Do you want to meet Lee Krasner?” I have frequently thought back to my response to that question, because if I had said no, my life would have followed an entirely different trajectory.

Two days later she was introduced to Lee Krasner. For the next few years, 1978-80, Landau jumped on Amtrak from Maryland to New York, doing interviews to write her dissertation. To do her research, Landau often stayed with Krasner at her Manhattan apartment, with ten days at her house in East Hampton in 1979. She also interviewed Reuben Kadish, Mercedes Matter, Illya Bolotowsky, and other artists in Krasner and Pollock’s circle. As Landau said,

One of the great things about being my age, my generation, is that a lot of these people were still alive and not too old to remember.

Landau described moments of what it was like being a full-time mother, writer, part-time teacher, and student during the late 70’s. Although it was stressful, through Landau’s lens of looking back, parts of it could have been scenes from a comedy:

In 1979, I had to be in New York City to be interviewed by Barbara Rose for a film on Krasner. Most of the time, I would drive my toddler son to my parents in Philadelphia, leave him there, and then keep going. But since I’d be staying in the city, I didn’t want to bring my car. I took my son on the train with his little suitcase, and when we arrived in Philadelphia, my mother was standing on the platform. I stepped off the train, handed her my son with his little bag, got back on the train, and kept on going up to New York.

There were several competitors to Dr. Landau in writing her dissertation on Krasner. Art historian and co-author of the Jackson Pollock Catalogue Raisonné, Francis V. O’Connor was instrumental in getting Krasner to permit Landau to be the one. She had eight formal interviews with Krasner during the research phase, not including follow-up phone calls. Although working with Krasner had its challenges, Landau was able to complete her dissertation, and years later used it as the basis for the early years covered in Lee Krasner – A Catalogue Raisonné.

To bring objectivity to writing about Krasner for her thesis, Landau said she began to think of her more as a fictional character than a real person. It helped to give her some distance from Krasner as an individual, yet write more personally about Krasner and artistic achievements.

When I asked Landau about what Krasner’s relationship was with Pollock, Landau explained,

My dissertation was on her early career up to 1956. Pollock's death was the sort of coda to that. I was talking to people about her art. I did ask people who knew them if they thought that Pollock was enthusiastic and supportive of her as an artist. I got very different answers. I concluded that Pollock was so insecure as a person and gave different answers depending on what he thought different questioners wanted to hear.

Grace Hartigan, for example, didn't think that Pollock had any real liking for her work. On the other hand, John Bernard Myers, who ran the Tibor de Nagy Gallery, told me flat out that under no circumstances would there have ever been a Jackson Pollock without Lee Krasner. I totally agree with that.

She kept him in the most important years of his career from being a drunk. But she also really understood what his revolutionary artistic techniques were all about. In correspondence I had with noted Abstract Expressionist critic Clement Greenberg, he agreed that Krasner was the most important influence on Jackson Pollock because she was so convinced of his importance.

Jackson Pollock

The first book for most scholars usually comes out of their dissertation. While Landau’s dissertation was about Krasner, when she interviewed people, many were more interested in talking about Pollock. As a result, she had a plethora of first-hand unpublished information about Pollock. In 1987, a door opened for Landau to write her first book.

The art historian Francis O'Connor approached me to write an essay about Pollock for a prominent art publisher, Harry N. Abrams, which he himself had been asked to produce. The manuscript had a strict limit of no more than 100 pages. O’Connor introduced me to the editor at Abrams and the next thing I knew I had a contract to write the essay. A few months later, I realized I was running way over the limit, so I called the Editor asking if she could look at what I had written and let me know how to cut it down. In a day or two, she called and said, “Tear up that contract. I don't want you to stop. I'm going to send you a contract for a completely different book.” So, my first book published in 1989 was on Jackson Pollock, which stayed in print from 1989 to 2022 and sold well more than 50,000 copies.

Among Dr. Landau’s notable discoveries was that Pollock was more influenced by the Mexican muralists than commonly understood. In 1930, Pollock drove with his friend Philip Guston to Pomona College just outside of Los Angeles to examine José Clemente Orozco’s mural, Prometheus, on the college dining hall wall. In 1932, Pollock’s friends from high school, Harold Lehman, Reuben Kadish, and Pollock’s brother Sande, worked with David Alfaro Siqueiros on a controversial mural, América Tropical, located on Olvera Street in downtown Los Angeles. Pollock went to see the mural on a trip home after he had moved east. A few years later, in New York City, Lehman invited Pollock to participate in the Siqueiros Experimental Workshop, where he was first exposed to the use of industrial paints and experiments of applying paint directly onto a support flat on the floor, rather than an upright panel or a canvas tacked to an easel. As Lehman said,

The methods used in the Siqueiros Experimental Workshop - the panels laid flat on the floor, the paint dripped, poured, and splattered, the use of the "accidental" and myriad other techniques - all find their echo in Jackson Pollock's later work - in particular, the so-called "Drip Period"... a period I think would be unimaginable without Pollock's Workshop experience.

Another important influence on Pollock discovered by Landau was the direct aesthetic impact of Swiss photographer and graphic designer, Herbert Matter. In 1943, Matter designed an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art called Action Photography, which Landau asserts had a key effect on Pollock’s method of “action painting.” In addition, Matter’s use of strobe lights distilled imagery in motion in a way that helped Pollock to reimagine his own application of paint on the canvas. Matter also introduced Pollock to art luminaries in the New York art scene, who had an impact on Pollock’s work. These included sculptor Alexander Calder, and James Johnson Sweeney, a MoMA curator and early promoter of Pollock’s work.

With all the hats Landau has worn in her career, research and doing oral histories by meeting with artists continue to be what interests her most.

I like detective work. I also like to write in a way that’s not dry, to write in a way that is more like a novel to grab the reader and get them involved in the story. For example, the first sentence of an essay I wrote on Pollock, Krasner, Herbert and Mercedes Matter published in 2007 was “As the women loved to tell it, they first met in jail.” (Both were arrested in 1936 for protesting the unfair firing of WPA artists and models.)

The Mexican Influence

A few years after Dr. Landau’s book on Pollock was published, she was approached by Jürgen Harten, Director of the Künsthalle in Düsseldorf, Germany. He was planning a joint retrospective on Pollock and Siqueiros for 1995. After meeting at the College Art Association in New York City, Harten asked Landau to write one of the essays for the catalog of the show.

It was through this project that Landau met the art historian and expert on the life and artwork of David Alfaro Siqueiros, Irene Herner. Herner’s parents were art dealers in Mexico City and represented his work (as well as the other two major Mexican muralists, Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco) so she knew and had grown up looking at Siqueiros’ paintings in her parent’s home. Hearing that Landau had never been to Mexico, Herner replied, “How can you write about the impact of the Mexicans on Pollock if you haven’t seen any of the murals?”

A few months later, starting in Los Angeles, they first went to Pomona College to see the Orozco mural that was so influential to Pollock in his formative years and then went to Olvera Street to see Siqueiros’ América Tropical mural (years before its restoration in 2010.) Landau and Herner became fast friends. When the Düsseldorf Museum sent Landau to do more research related to Siqueiros in Mexico City, Herner insisted on having Landau stay the weekend with her at her home in Tepoztlán, the first of many visits since then.

Morelia Mural by Guston and Kadish

From 1982 to 2013, Dr. Landau taught in a joint Art History program between Case Western Reserve University and the Cleveland Museum of Art. Another topic of interest, which Dr. Landau wrote about, is the impact of Mexican art on Philip Guston, a boyhood friend of Jackson Pollock, Harold Lehman, and Reuben Kadish.

Her interest was piqued in 2002 when the Cleveland Museum of Art exhibited a major retrospective of the third famous Mexican muralist, Diego Rivera. A symposium was planned with guests coming from Mexico and all over the world. Landau stepped up to write and do a presentation about Rivera and his artist wife Frida Kahlo, focusing on the portraits they did of themselves vs. the portraits they did of each other. While doing research, Landau came across a 1993 Yale University/Smithsonian American Art Museum catalog called South of the Border: Mexico in the American Imagination, which included a photo of the central panel of the mural, The Struggle Against Terrorism, by Guston and Kadish, done in 1934 – 35 in Morelia, Mexico. Landau recalled:

I had no idea that this mural existed. So here I am interested in Pollock and the Mexicans, but I had no idea that Guston had ever been to Mexico and co-created this mural. When I made a list of places I wanted to get permission to go to and take photographs for the Cleveland project, I added Morelia to the list, even though it had nothing to do with Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo.

Although Dr. Landau had read Musa Mayer’s book, Night Studio, about her father, Philip Guston, as well as Dore Ashton’s book, Yes, But – A Critical Study of Philip Guston, the mural Guston worked on in Morelia was barely mentioned. In 1934, when he, Kadish, and their writer friend Jules Langsner, took the offer to go to Mexico to create a mural, Guston was still using his birth name, Phillip Goldstein. Because of the name change, Dr. Landau recounted, “For years, Guston didn’t admit to having anything to do with that mural.”

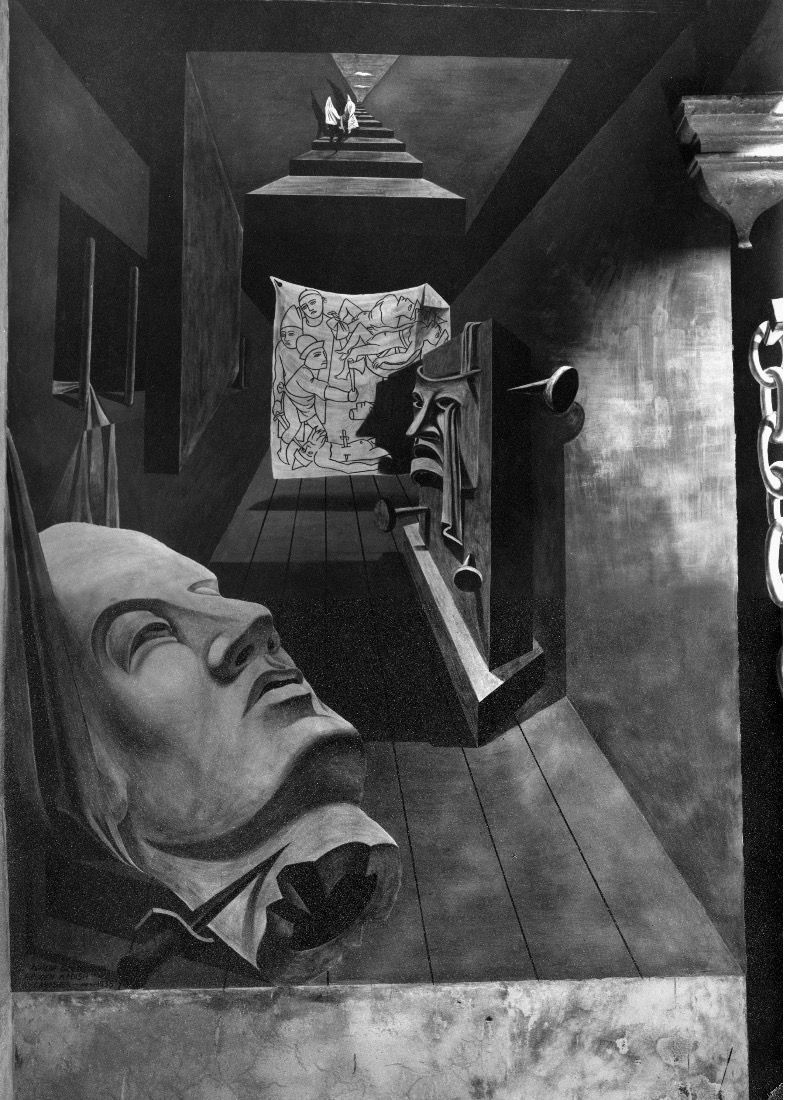

With Herner’s help, a driver was hired to take Landau and her husband to Morelia to see the mural (the first of four trips she would take there). Originally the mural was painted at the site of a late-18th-century Baroque palace in Morelia, Mexico. Eventually, the building became a museum on the college campus of the University of San Nicolas Hidalgo. Unavailable for viewing for roughly half a century, in the 1970s, there was a leak on the patio where it was located. When workers came to fix it, they realized that a fake wall was covering something. Once the wall was removed, they were stunned to find the mural behind it. Landau recalled:

Except for the lower left panel that had destruction from saltpeter, which had been leaching through for decades, the mural was in pretty good shape. At that time, I didn't know that much about Kadish's work. However, when I got back from that first trip, I found out through Stephen Polcari, who at that time was the Director of the Archives of American Art in New York, that the AAA had just acquired Kadish's papers. I went to New York, and I was blown away because there were all these black-and-white installation photographs from just after the mural was completed, which revealed things that I could barely see at the site.

In Mexico and American Modernism, Landau describes in detail the results of her detective work and startling revelation in deciphering the imagery of this massive 40-foot fresco mural, painted in the styles of Italian Renaissance art and California Post Surrealism. Amongst numerous depictions of brutality and torture throughout, hidden in a somewhat inconspicuous place in the lower left panel was a small cartoon, which she figured out was based upon an anti-Semitic woodcut done in 1475 by Albert Kunne, known as the Burning of the Jews of Trent. Landau recalls,

One of the first things I saw from the installation photographs of the mural were the images of people wearing pointed hats. When I asked the Museum Director if this came from some kind of Hispanic codex, he assured me that this imagery related to Mexican campesinos, or peasant farmers being punished by Catholic priests. While the medieval robes and headgear certainly reflected Catholic priests, I knew that the pointed hats of the victims were a definite marker for Jews in medieval times.

It took me a year of research looking at all kinds of medieval representations of Jews until I came across the woodcut by Kunne. The image Guston and Kadish had placed in their mural was an almost identical replica of Kunne’s 15th-century composition.

In Mexico and American Modernism, Landau writes:

…Guston and Kadish increased Kunne’s level of violence and affliction beyond the wheel and flame-stick, depicting the dead elder Moses being stabbed by one of the Catholic torturers . . .indicating the young Jewish artists’ advanced level of rage.

The history of this woodblock print by Kunne goes back to 1475, when the Jews living in Trent, a city in northern Italy, were wrongly accused of killing a Christian baby, supposedly to make matzah with his blood. Since the Mexican authorities in 1934-35, would likely not have understood such a reference, Guston and Kadish used and accelerated its horror to make a secretly meaningful statement. Dr. Landau explains:

Accusations of Blood Libel had spurred the famous Kishinev pogrom a few years before their parents left the Pale of Settlement, the arrest of Mendel Beilis in 1911 (and his notorious trial in 1913) had caused an international scandal. The Nazis were reviving this slanderous aspersion in the propaganda periodical Der Stürmer at precisely the time Guston and Kadish were painting in Mexico.

A more personal historical parallel to this event occurred in 1932, when Guston, Kadish, and Lehman, as members of the Bloc of Painters in Los Angeles, created portable murals, several of which were trying to expose the wrongful accusation of rape against, a group of black teenagers, known as the Scottsboro Boys, riding hobo on a train in Alabama in 1931. The artists were also privy to KKK terrorism against Jews in Los Angeles during the Depression. Unfortunately, the current rise of antisemitism includes parallels that go back to such events.

Relevance of Pollock today

As we enter the 21st century, with the advent of so many new artists and mediums, from painting to AI in galleries, museums, and online, I asked Dr. Landau how, in particular, the artwork of Jackson Pollock is relevant today. Landau replied,

Earlier in the 20th century, Picasso was the artist that everybody compared themselves to. Then it became Pollock. And in a lot of ways, still is. In the 1940s and early fifties, people thought that the only thing that made Pollock special was his drips and splatters on the canvas. But Pollock's importance has more to do with the fact that he was really the progenitor of the idea of art as a performance/situation. The process is what the work is all about.

Even rejecting what Pollock was doing is important. As an artist, you're either accepting or you're rejecting and creating something new.

Today, interest in the work of Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner, and Philip Guston has not waned. In 2012, Pollock’s painting, Mural, came to the Getty for study and conservation. In 2014, when the restoration was completed and exhibited to the public, Mural received the second largest audience of any show at the Getty to that date even though it consisted of only one painting and a roomful of didactic information on its conservation.

Interest in the Abstract Expressionists is still at an all-time high, with a great deal more attention now being paid to women painters like Krasner, overlooked and understudied for decades, a topic which is Landau’s current focus. Co-author of Abstract Expressionists: The Women, (published in London in 2023) she is acting as guest curator of a show of women abstractionists that will travel around the United States in 2025 – 2027 (see details below).

I agree with Landau when she says, “Abstract Expressionism is still very important today.”

Abstract Expressionists: The Women, The Levett Collection (London: Merrell, 2023); co-authored with Joan M. Marter. Note: A traveling exhibition based on the book is taking place from 2025 – 2027. Opening at the Wichita Museum, the show will also appear at the William and Mary Museum in Williamsburg, Virginia; the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art in Madison Wisconsin; Mobile Museum in Mobile Alabama, and Grinnell College Museum of Art in Grinnell, Iowa.

Epilogue: Michael West’s Monochrome Climax (NY: Hollis Taggart, 2021)

Space Poetry: The Action Paintings of Michael West (NY: Hollis Taggart, 2019)

Lee Krasner: Charcoals (NY: Kasmin, 2019)

Mexico and American Modernism (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2013)

Pollock Matters (Chestnut Hill MA: McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, 2007); co-edited with Claude Cernuschi

Reading Abstract Expressionism: Context and Critique (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2005)

Lee Krasner: A Catalogue Raisonné (NY: Harry N. Abrams, 1995); assisted by Jeffrey D. Grove

Jackson Pollock (NY: Harry N. Abrams and Thames & Hudson, London, 1989); latest reprint 2010